Content warning: death, the corpse, suicide, mortality.

Written by Hannah Owen for ARTHIST 334: Ways of Seeing Contemporary Art at University of Auckland, taught by Gregory Minissale, 2022.

Grade: A+

The Art of Dying –

Confronting death through depictions of the human body in Contemporary Art.

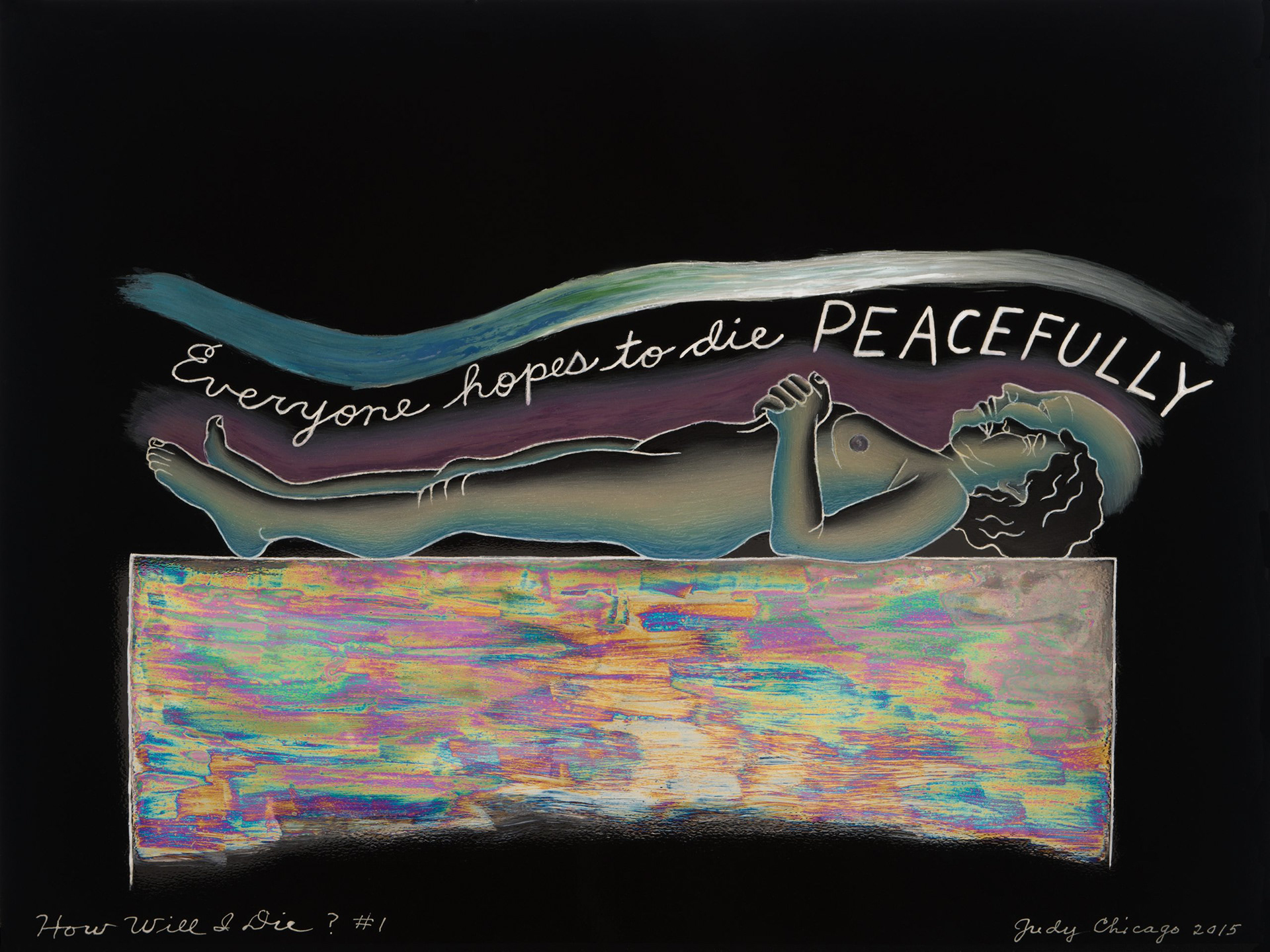

Figure 1 - Chicago, Judy. How Will I Die? #1, from The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, Mortality. 2015. New York. Kiln-fired, painted black glass, 9 x 12 inches. Image courtesy of the artist via judychicago.com.

Figure 2 - Serrano, Andres. Rat Poison Suicide from The Morgue. 1992. Medium-format photograph. Image courtesy of the artist via andresserrano.org.

Figure 3 - Serrano, Andres. Burnt to Death from The Morgue. 1992. Medium-format photograph. Image courtesy of the artist via andresserrano.org.

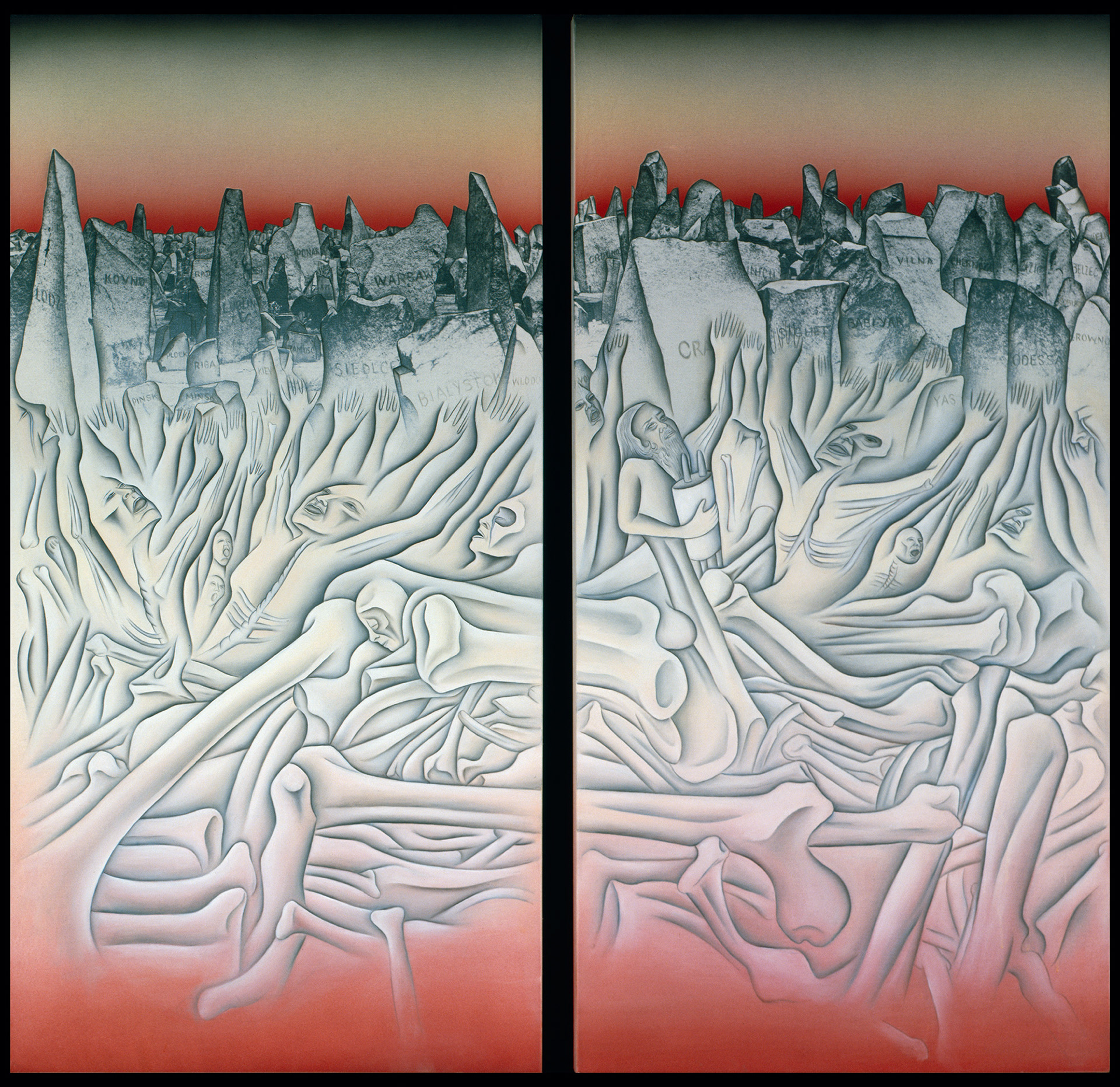

Figure 4 - Chicago, Judy. Bones of Treblinka, from Holocaust Project. 1988. New York. Sprayed acrylic, oil, and photography on photolinen, screen printing and fabric on photolinen, 48.5 x 50.5 inches. Image courtesy of the artist via judychicago.com.

The certainty of death is one of the few things that unites every human being, yet facing death is an individual experience – some are fearful, while some live to die. Artists throughout history have illustrated this taboo subject using memento mori[1] motifs; however, it is within Contemporary Art where we are confronted with the reality of death. In this essay, I will be looking at two contrasting artists who have explored these themes in their oeuvre: Judy Chicago and Andres Serrano. Both artists unusually depict the human body by visualising the experience of dying, and I will investigate how they encourage the viewer to contemplate and be confronted by death in different ways. By analysing Chicago’s How Will I Die? #1 and Serrano’s Rat Poison Suicide, we can see how certain depictions of the body can encourage the viewer to contemplate their mortality. In contrast, Serrano’s Burnt to Death and Chicago’s Bones of Treblinka confront the viewer with death in inescapable and powerful ways.

Andres Serrano, known for photographing controversial subject matter, fostered a curiosity surrounding the dead. Armed with a black backdrop, flash, tripod, and a Mamiya RB67 camera, Serrano was allowed into a morgue to photograph his series, The Morgue (1992). In response to the controversy surrounding his access, Serrano explains, “…we will all be let in one day. I think you’re upset and confused that I’ve brought you there prematurely”.[2] Avoiding touching or manipulating the bodies, aside from placing cloths over faces to preserve anonymity, Serrano left everyone as he found them. An intentionally voyeuristic series, The Morgue captures death in all its forms: eerily clean bodies appearing as if they are simply asleep, situated alongside burnt bones, decomposing flesh, and fatal wounds. The faceless bodies are devoid of all identifiers, forcing us to consider that these bodies could be anyone, me, you, or all of us.[3] Emotionally charged and disturbingly aesthetically pleasing, Serrano encourages the viewer to consider life and death. He acknowledges that it can be very frightening to encounter these images and face the reality of death. However, he argues that these bodies are not just mere corpses to him – they are “not inanimate, lifeless objects”, and he believes he has captured “life after death, in a way”.[4]

Judy Chicago, also drawn to subject matter that is controversial and absent from mainstream dialogue, has explored life in all its forms. She has visualised the human condition from birth to death and everything in between. In the mid-1980s, Chicago and her husband, photographer Donald Woodman, embarked on a journey to learn about their Jewish heritage and the Holocaust. One of the greatest tragedies in human history, the Holocaust, was unexplored in Contemporary Art. Chicago and Woodman believe that “…confronting and trying to understand the Holocaust, as painful as that might be, can lead to a greatly expanded understanding of the world in which we live.”[5] For Chicago, it was important for the works in the Holocaust Project (1985-93) series to remain historical but emphasise the people and their actual experiences, feelings, and fears.[6] Chicago more recently has begun to meditate on her eventual demise. After a potentially serious health scare in 2012, she was driven to research and create an extensive series, appropriately titled The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2012-2019). She learned that earlier societies did not practice the denial and silence about the experience of death that is common in the world today[7] and illustrated her journey through her understanding of death. Within The End, she created a subseries titled Mortality, consisting of 15 small kiln-fired paintings on black glass. It begins with philosophical musings and moves into a collection of personal questions about how the artist might die – Will I leave as I arrived? Will I be contorted in the throes of death? No one wants to die hooked up to machines in a hospital. These phrases, accompanied by self-portraits in varying stages of death, encourage the viewer to begin to question their own life. We see ourselves as the figure in the works and wonder – How will I die?

Both Chicago and Serrano approach death in contrasting ways, but both have examples of intentionally using the body as a vehicle to contemplate death. Chicago’s How Will I Die #1, 2015 (fig. 1), begins a series of works where she explores her mortality through self-portraiture. She takes us on a journey with her, encouraging us to apply the same questions to our lives and come to terms with the inevitability of death. Chicago paints her naked, aged body lying quietly on a rectangular oil-slick plinth. This image is not a ‘nude’ – what we are seeing is a woman who, although portrayed tastefully, is vulnerable and exposed. She appears asleep with her eyes closed and hands clasped under her breasts. Her body is posed intentionally, as if for an open-casket funeral. There is hand-written cursive, floating like a thought, following the body’s contours, reading: ‘Everyone hopes to die PEACEFULLY’. We see a translucent, bald head rising from the physical body, visualising the soul leaving the material form or entering the afterlife. This portrait appears to illustrate the exact moment of death. We begin to question how Judy[8] has died. We are given no clues, only that she hoped to die peacefully. The word ‘everyone’ encourages the viewer to place themselves into the portrait and contemplate if we will die peacefully too, and if not, how we might go. The black glass used is a strong yet fragile medium that Chicago uses intentionally to metaphorise the human condition and considers an appropriate colour for a dark topic.[9] It isolates the body in the centre, and, although we get a sense of gravity from the holographic plinth Judy lies on, we feel as if she is floating in a void.

Serrano composes a similar image with Rat Poison Suicide, 1992 (fig. 2), but it is far more ambiguous. We see similar treatment with the use of a black background as a void, perhaps a visual hint at death in an image where that is not so clear. This is an image of a woman who, at first glance, appears to be waking from sleep on a cold winter’s morning. She is on her back, covered in goosebumps, and her arms are crossed and raised above her chest. The frozen nature of photography makes us wonder if Serrano has captured movement. Chiaroscuro treatment of the flesh, intentional draping of fabric, and intimate clothing on her body distract from the reality of the image. Whereas in How Will I Die #1, we are met with a definite image of the moment of death, in Rat Poison Suicide, we are not initially aware we are looking at a corpse. The photograph’s title is our only obvious clue that this woman is no longer living. It is unsettling when we learn her cause of death was suicide – the only way a human has control over their own demise. The contrast between the apparent turmoil in her life and her peace in death is extremely confronting, especially for those who have battled with mental health and suicidal ideation. Serrano intentionally crops the body in the frame, disconnecting us from the fact that this is a whole, dead, human body. The introduction of studio lighting and a backdrop into the morgue further alienates the subject. This forces us to see the image first for its aesthetic qualities and not for its reality, which can be upsetting and confusing upon realising what we are looking at. Minisalle describes the treatment of the corpse in Serrano’s works as sculpted flesh that distracts from its decomposing nature and emphasises the beauty of the body, even in death.[10]

Visualisations of death are not always treated as delicately as How Will I Die? #1 and Rat Poison Suicide. Another work from Serrano is Burnt to Death, 1992 (fig. 3), where we are confronted by a dirty and raw photograph of the corpse. It is a disturbing image of the charred remains of a body, viewed from the neck up. We see the entire head, which is unusual – there is no need for Serrano to preserve the anonymity of this corpse as the cause of death has done that already. The shallow depth-of-field highlights the structure of the skull, and the harsh lighting emphasises the dark cavities on the face. We often hear the phrase, ‘the eyes are the window to the soul,’ but when we look into the eyes of the subject, we are met with nothing. Where Serrano previously used the background to represent a void, he appears to have done the opposite here. The backdrop is creamy white cloth, and the remains are charred black – in this instance, the body is the void. The blackened bones and burnt flesh have immediate connotations with fire, and we cannot help but visualise a person engulfed in flames. Serrano found that most of the bodies he photographed died tragic, violent deaths,[11] and while we all hope to slip away peacefully, this is not always the reality.

While Serrano’s imagery is centred on the individual body, Chicago has explored death and dying on a historical scale. She believes that private tragedies tend to pale in comparison to the enormity of the tragedy of the Holocaust,[12] and as part of her series on the topic, she created Bones of Treblinka, 1988 (fig. 4). Primarily blood red and bone white, Bones of Treblinka is a diptych depicting human bones merging with bodies contorted in agony, clawing upwards as they cry for help. In the upper-third of the work are jagged grave-like stones with names of the dead, as they appear at the memorial site in Poland. This is a still work, yet we can sense the writhing bodies and the moans in anguish. This is a confronting visualisation of Jewish genocide and suffering. Seeing the human body depicted in this way, knowing the atrocities of the Holocaust and the devastation it caused to humanity, it is difficult not to be moved by this work. It visualises feelings of helplessness and fear surrounding death. Chicago acknowledges that it is difficult to relate to a pile of bones, but by actively putting yourself and the people you know into the work, it becomes incredibly vivid.[13] It is easy to consider an atrocity like the Holocaust purely as history, however, when you are encouraged to put yourself into the position of others, it becomes hugely confronting and upsetting. Bones of Treblinka emphasises the lack of choice surrounding death and the fear that someone or something can take your life away from you against your will. This not only applies to the Holocaust but also to war, homicide, genocide, and even terminal illness.

Through depictions of the human body, the subject of death in Contemporary Art is interesting and unsettling. We are confronted by a universal experience that tends to be considered taboo or unsavoury. However, through works from artists such as Judy Chicago and Andres Serrano, we can begin to accept the inevitable. It helps both the artist and viewer understand the contemplative, confusing and confrontational facets of human death and dying that are not openly discussed in our society. We tend to fear death because it is an unknown, but if you allow yourself to be exposed to death in all its forms, you learn to fear it less. No matter what happens in our lives, it will always come to an end; Memento mori.

Footnotes –

[1] Latin phrase meaning ‘remember you must die’. Common symbolism seen in art include the skull, hourglass, fruit, and flowers – representing that all must come to an end.

[2] Serrano, Andres, interview by Anna Blume. 1993. Andres Serrano by Anna Blume - Bomb Magazine (February 3, 5).

[3] Minissale, Gregory. 2011. "Deleuzian Approaches to the Corpse: Serrano, Witkin, and Eisenman." Janus Head 12 (2): 101-129.

[4] (Serrano 1993)

[5] Chicago, Judy. n.d. Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985-93). Accessed March 2022, via judychicago.com.

[6] Chicago, Judy. 2021. The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago. New York: Thames & Hudson.

[7] (Chicago, The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago 2021)

[8] For the purpose of this essay, I refer to the self-portrait as ‘Judy’ to separate the artist from the portrait.

[9] (Chicago, The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago 2021)

[10] (Minissale 2011)

[11] (Serrano 1993)

[12] (Chicago, The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago 2021)

Bibliography –

Chicago, Judy. n.d. Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985-93). Accessed March 2022. https://www.judychicago.com/gallery/holocaust-project/hp-artwork/.

Chicago, Judy. 2021. The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago. New York: Thames & Hudson.

Minissale, Gregory. 2011. “Deleuzian Approaches to the Corpse: Serrano, Witkin, and Eisenman.” Janus Head 12 (2): 101-129.

Serrano, Andres, interview by Anna Blume. 1993. Andres Serrano by Anna Blume - Bomb Magazine (February 3, 5).

Image List –

Figure 1 - Chicago, Judy. How Will I Die? #1, from The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, Mortality. 2015. New York. Kiln-fired, painted black glass, 9 x 12 inches. Image courtesy of the artist via judychicago.com.

Figure 2 - Serrano, Andres. Rat Poison Suicide from The Morgue. 1992. Medium-format photograph. Image courtesy of the artist via andresserrano.org.

Figure 3 - Serrano, Andres. Burnt to Death from The Morgue. 1992. Medium-format photograph. Image courtesy of the artist via andresserrano.org.

Figure 4 - Chicago, Judy. Bones of Treblinka, from Holocaust Project. 1988. New York. Sprayed acrylic, oil, and photography on photolinen, screen printing and fabric on photolinen, 48.5 x 50.5 inches. Image courtesy of the artist via judychicago.com.