Written by Hannah Owen for COMMS 302: Visual Communication at University of Auckland, taught by Laurence Simmons, 2022.

Grade: A+

Giovanni Bellini’s Sacred Allegory –

A visual analysis.

Figure 1 – Giovanni Bellini's 'Sacred Allegory,' c.1488

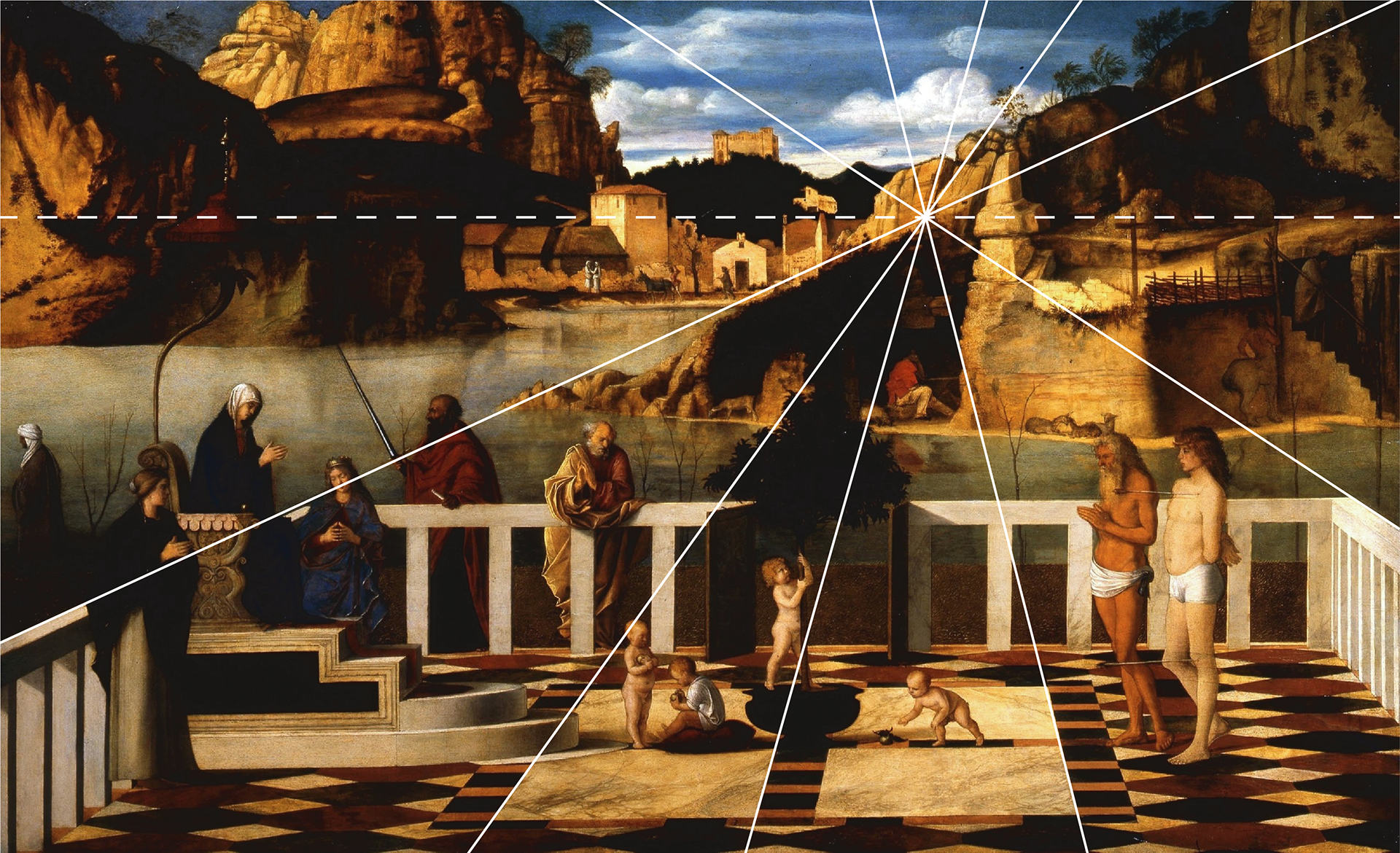

Figure 2 – Example of the lines of perspective leading to a single vanishing point in 'Sacred Allegory'

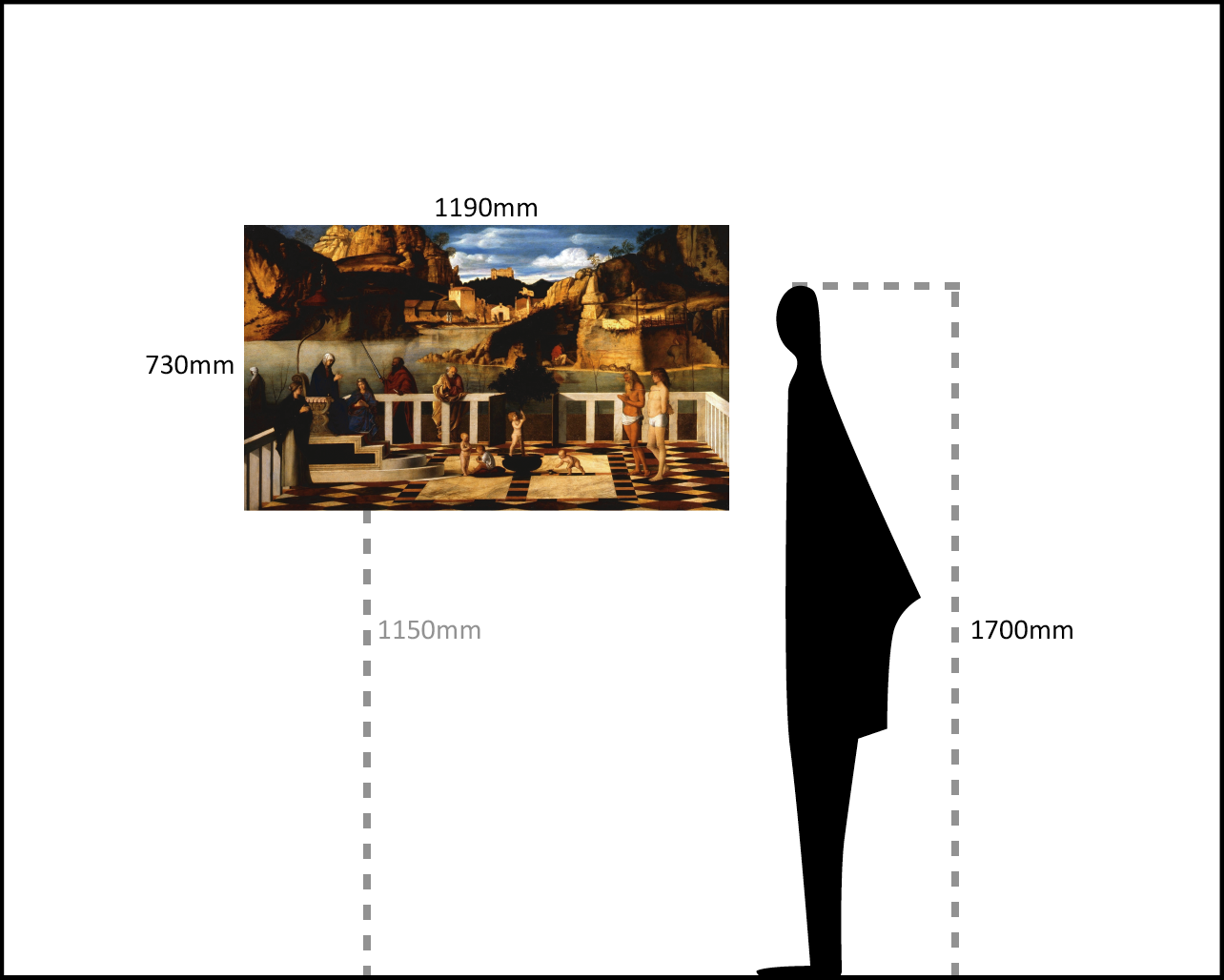

Figure 3 ¬– Example of the true scale of 'Sacred Allegory' compared to an average human height

Figure 4 – Details from 'Sacred Allegory'. From left to right: Saint Job, Saint Sebastian, Anthony Abbot

Figure 5 – An example of a sacra conversazione, in Giovanni Bellini's 'San Zaccaria Altarpiece,' 1505.

Art in the Italian Renaissance was not as simple as a beautiful image. Artworks always served a functional and meaningful purpose and were usually commissioned by patrons to suit their individual needs. The motivation for a patron to commission an artwork varied between the pleasure of possession, civic consciousness, self-commemoration, and to showcase active piety.[1] This meant that for artists in quattrocento[2] Italy, art-making had little to do with the pleasure of the craft. The subject of paintings varied from Christian devotional imagery, commemorative portraiture, and classical allegories painted in traditional tempera. The first Italian city-state to transition into the use of oil paint as their artists’ primary medium was Venice. Venice was the richest, most comfortable, best governed, and securest of all the city-states.[3] Venetians were isolated in their politics, religious ordinance, dress, customs, and manners due to their geographical location; they were considered “unique and peculiar”[4] by other Italians. Regardless, they held a tremendous amount of civic pride. Master painter Giovanni Bellini grew up in and spent most of his life in Venice in the fifteenth century.[5] He was surrounded by talented and successful artists, including his father Jacopo Bellini, brother Gentile Bellini, and brother-in-law Andrea Mantegna. Everything Bellini did was rooted in his locality,[6] and he held the respect of the Venetian people and the patronage of the State.[7] The context of his oeuvre can be described as Venetian humanism and spirituality.[8] With these points in mind, we can discuss Sacred Allegory (figure 1), painted circa. 1488. This is one of the few Renaissance paintings in which we cannot be sure of the intended motivation, function, or audience. The title, Sacred Allegory, is our only suggestion regarding the painting's content. Still, it is deliberately ambiguous as it is not a title given by the artist himself, nor can art historians agree on a more definite title. ‘Sacred’ is defined as something dedicated to a religious context and made holy by association with a god[9], and ‘allegory’ is defined as the use of symbols in a story or picture to convey hidden meaning; symbolic representation. [10] We can then interpret ‘sacred allegory’ to simply mean a story or image of religious symbolism. Through formal and contextual visual analysis, I will be exploring this enigmatic painting to discover its potential purpose, function, and meaning.

The composition of Bellini’s Sacred Allegory, now located in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, can be split horizontally into three main sections. The foreground contains a large, quadrilateral terrace with three visible sides, surrounded by a cream-white balustrade. The floor is paved with red, yellow, and brown tiles reminiscent of those found inside Venetian churches at the time.[11] Various saints and figures occupy the terrace. Implied by the title of this painting, we know that these figures are religious, and therefore we can determine who they are. On the left, the Virgin Mary sits atop a four-stepped throne shaded by an ornate red baldachin. With her head tilted down, she closes her eyes and holds her palms together in prayer. She is flanked on either side by two other women. The woman on Mary’s left is thought to resemble Catherine of Alexandria, shown with a diadem on her head,[12] dressed in a rich blue cloak, and her red hair falling loosely on her shoulders – a typical portrayal of unmarried Renaissance women,[13] as Catherine was. The woman on Mary’s right could be Mary Magdalene, but this is contested. Delaney argues that she is a personification of the Christian virtue of Hope[14] which she connects to the tree in the centre of the terrace. She discusses the three virtues as the latitude (Charity), longitude (Faith), and altitude (Hope) of the cross, and the tree as an “allusion to the wooden Cross of Christ… a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice,” aligning the tree with the virtue of Charity and to its placement in the centre of a tiled cross on the floor of the terrace.[15] The tree could also represent the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, found in the Garden of Eden in the Book of Genesis.[16] Around this tree are four children, one of whom is likely the Christ Child, as he is clothed and seated on a cushion – making him the only figure in the foreground, other than Mary, who is seated. He contemplates a golden apple while a putto[17] stands before him, holding another apple and waiting with anticipation to give it to Christ. Another putto stands with his feet firmly planted in the pot that the tree grows from, shaking the tree to cause the apples to fall. A third putto reaches for a golden apple that has fallen to the ground. The putti are thought to represent Jesus’ first martyrs – the Innocents – who King Herold massacred in Bethlehem.[18],[19] The putti provide the only feeling of movement in an otherwise still and quiet composition. To the left of the putti, the final figures depicted on the terrace are Saint Job and Saint Sebastian. Saint Job is an Old Testament hermit saint, identifiable by his tanned skin and uncouth appearance,[20] and was venerated in Venice.[21] The martyr Saint Sebastian is identified by his pale skin, luscious hair, and the arrows protruding from his chest and knee. He is the only adult figure on the terrace who does not hold his hands in front of him in prayer as his hands are tied behind him.[22] He is also a venerated saint in Venice. Behind the tree is an opening in the balustrade linking this silent and ‘spiritual’ terrace to the material world behind. Directly outside the balustrade, we see Saint Peter, dressed in yellow and leaning over the railing in prayer. Saint Peter was one of the twelve apostles of Christ and an early leader of the Christian Church. Moving left, we see Saint Paul, identified by the scroll held in his left hand and the Sword of Martyrdom[23] in his right. Saint Paul was known for spreading the teachings of Christ and the Church, which may help explain the unidentified oriental figure departing to the far left. It is speculated that the figure is a pagan being turned away by Paul for declining the ‘true Faith’.[24] Peter and Paul are intentionally isolated behind the balustrade. They are considered instruments of the Lord’s earthly mission and thus stand on the edge of the material and spiritual realms.[25] Moving into the midground, we are met with a naturalistic, rocky landscape surrounding a lake – this is the earthly, material realm. Bellini was known for painting what was known to him,[26] so there are likely strong Venetian influences in the scenery. The lake appears dense and misty, indicated by reflections in the water that are not sharp or detailed and only give us blurs of colour.[27] Moving along the landscape to the left, we find a large cave or shelter in which an unidentifiable figure rests. It is assumed by the presence of goats along the water’s edge that he is a shepherd.[28] Atop the cave is a cliff with what appear to be ruins. A wooden cross stands tall on the edge of the cliff. This helps reiterate the Christian symbolism on the terrace and ties the midground to the events in the foreground. On the right edge of the painting, we can see a cloaked figure descending the stairs towards a centaur in the shadows. The placement of these two characters together allows us to identify the cloaked figure as hermit saint Anthony Abbot.[29] The centaur guided Anthony through the Thebaid desert to the Monastery of Saint Paul,[30] who is depicted to the left of the terrace in the foreground. Anthony was also associated with Charity,[31] consistent with the terrace's symbolism. Finally, we can see Venetian-style architecture lining the shore in the background. There are pastoral figures, perhaps conveying a sense of well-being and harmonious existence between the spiritual and natural world.[32] Behind this is densely forested hills, upon which a monumental structure sits – perhaps a monastery. The sky is a bright blue with scattered white clouds, appearing inconsistent with the golden light illuminating the scene. Every detail of Sacred Allegory is intentional, meaning that the golden light might represent the spirituality of the allegory and allude to God’s presence. However, while the individual elements of the Sacred Allegory have been discussed in detail, no coherent overarching concept has emerged.[33]

While it is essential to understand the subject matter in a close reading and visual analysis of Sacred Allegory, it is necessary to consider the role of form and form’s relationship to the subject. This painting is an example of one-point perspective which was introduced in the Renaissance and revolutionised painting techniques and styles from then onwards. Baxandall describes this perspective style as simple: “…the painter made his flat surface very suggestive of a three-dimensional world… Vision follows straight lines, and parallel lines going in any direction appear to meet at infinity in one single vanishing point.”[34] In Sacred Allegory, the vanishing point is located precisely at the tip of the cave in the midground, and as a result, this is where our gaze meets the painting (figure 2). The vertical line of the edge of the cave opening leads our eye down towards the terrace, along past the Christ Child to Mary on her throne. Once our vision has taken this split-second journey, we freely gaze upon the rest of the image. It is significant to note that the vanishing point is directly in line with the tip of the wooden cross to its right,[35] which allows the subtlety of the form to stand out. The perspective also emphasises the contrasting geometry within the composition. The terrace is linear and consists of strict verticals, horizontals, and diagonals determined by its location in relation to the vanishing point; The landscape outside of the terrace is naturalistic, with organic and rough forms typical of rocks and erosion. However, nature itself partakes in a geometrical perfection[36] – particularly in the midground, we see the cave conforming to the lines of the perspective, the corner of the cliff shaped in a soft right-angle, and the shape of the stairs. On the terrace, we can identify gentle curves in the putto bending to take the apple from the ground, Christ’s back and Mary’s shoulders.[37] As a result, the differing sceneries remain balanced while still emphasising their divide.

The use of oil paint was another revolutionary addition to Renaissance art, with its usage first documented in Venice. Artists could produce a dense build-up of rich colours and layering, producing greater tonal density and volume.[38] This allowed Bellini to create a painting diffused with light and remarkable use of colour to emphasise texture and form. His colour palette is warm-toned, highly saturated, and dominantly yellow hues, with minor areas of blue and red. The warm yellow tones endue the composition with a serene feeling of warmth and sunlight “like that of an early morning in June.”[39] The oil paint allows the atmosphere to become form itself, creating a subtle density that unites all elements of the composition. Sunlight comes from the left of the frame and is strong and direct, as emphasised by the chiaroscuro treatment of the landscape. Interestingly, the intensity of the shadows does not appear to be replicated on the flesh of the figures on the terrace; instead, the light is consistent and seems to bask the area. The strongest shadows are cast by Mary and Christ, the only two ‘humans’ on the terrace, emphasising the difference between the material and spiritual.

The figures and the terrace are comparatively small to the rest of the image, occupying less than half of the composition. The painting is landscape-orientated, meaning that, despite its religious connotations, it was not an altarpiece. Its dimensions also indicate that it cannot have been held in your hand as a tool of private devotion as it was too large.[40] Despite its size, the treatment of the figures indicates that the painting may have been made to view in close quarters and privately. While today we are used to images composed in such a way, this was not common at the time. Looking with Baxandall’s ‘period eye,’[41] we could infer that this was painted for a studiolo[42] - where “reflection on art itself was as important as the reflection on the content of the painting.”[43] Norbert Huse suggested Isabella d’Este, one of the only major female patrons of Renaissance Italy and known patron of Bellini’s brother-in-law Mantegna, as the recipient of the painting, but this is widely disputed.[44] Regardless, we can assume that this painting served a function of both piety and pleasure. The gazes within Sacred Allegory are disconnected and distant – there is no eye contact between the figures, and they do not look at us. One could consider this a voyeuristic image, but although the figures do not look at us as we look at them, they are aware of our presence just as they are aware of each other on the terrace. We only see three sides of the terrace, inviting the viewer to become a passive onlooker. As indicated in figure 3, the average viewer of the painting would be looking down on the terrace, perhaps alluding to our position on an unseen, rocky landscape in which we coexist with the spiritual terrace below us. We may alternatively be located on the edge of the balustrade, just as Peter and Paul are. This would align the viewer with the two saints who, as mentioned previously, signify both the material and spiritual realms. This could indicate the portrayal of the unknown patron’s dedication and piety, as they would be comparing themselves to saints.

We do not know for whom or for what purpose Bellini painted Sacred Allegory, but we know that Bellini’s styles and iconography are understood in connection with Venetian Renaissance civilisation;[45] therefore, we can look at the historical context in which this work was created. In early 1485, a severe plague epidemic broke out in Venice and, as a result, the services of plague saints would have been in higher demand.[46] Sacred Allegory depicts three plague saints – Saint Job, Saint Sebastian, and Anthony Abbott (figure 4). This painting may have been commissioned as a prayer for protection against the plague or in gratitude for survival.[47] Their presence, and the paintings terminus ante quem[48] of 1488,[49] provides a unique and undeniable connection reflecting the specific needs of the quattrocento Venetian citizen.

Sacred Allegory may also be an alternative perspective of a sacra conversazione. Lindemann wrote on this extensively, describing that the arrangement of figures in Sacred Allegory closely follows the principles of the genre.[50] A sacra conversazione is a style of Renaissance painting in which the Virgin Mary and Child sit among an informal grouping of saints, which is demonstrated in the San Zaccaria Altarpiece by Bellini from 1505 (figure 5). This becomes plausible in Sacred Allegory if the viewer is encouraged to rotate the composition, so we visualise the scene from the right-hand side of the terrace. Once this is achieved, Mary is central, and saints flank either side. Due to this change in perspective, the disconnection between the figures is eliminated, and they appear closer together.[51] This means we are now looking into the light, which would be providing a golden, ‘holy’ glow behind Mary and the even illumination on the terrace. Lindemann explains that the essence of a sacra conversazione consists of a lack of thematic clarity – “the community of saints are shown in a timeless context rather than as part of a narrative.”[52] This theory would explain the unidentifiable narrative and purpose of the Sacred Allegory; however, it does make us wonder why Bellini would intentionally alter the viewpoint. Bellini did not like to be given strict instructions when painting, supposedly telling Pietro Bembo that he “always liked to wander at will in his paintings.”[53] The unfamiliar foreground with familiar nature in the background suggests we are looking at a fantasia or poesia[54] – a result of the mind wandering freely.[55] Bellini’s familiarity with the Venetian landscape and contexts and his familiarity with other Renaissance artists and their works means that the twist on the sacra conversazione may have been a subconscious decision as he ‘wandered freely’ through the painting. Land elaborates by stating that the truths of religion and nature “must be contemplated in conjunction with, not at the expense of, phantasy.”[56]

While the purpose, motivation, and contexts surrounding Giovanni Bellini’s Sacred Allegory are unknown and contested, it remains clear that this is an image of the Christian Church within a Venetian Renaissance framework.[57] Various Christian saints and figures adorn a symbolism-rich terrace within a golden, rocky landscape, inviting the viewer to observe the stillness and silence of the scene. Sacred Allegory was likely a painting for private use, and the unknown patron may have viewed it for pleasure, piety, and Venetian civic pride. Bellini shows us just how revolutionary the Italian Renaissance was in art history with his use of perspective and oil paint. He challenged the typical narrative function of art to create an ambiguous allegory that specialist art historians over five hundred years later cannot decode, with some considering it an alternative perspective of the sacra conversazione. Bellini was one of the great masters of the Italian Renaissance and was considered the ‘pioneer’ of cinquecento[58] art, paving the way for artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Giorgione, and Titian. Sacred Allegory is one of the many examples from Bellini’s oeuvre that help contemporary art historians define and understand the Renaissance through a ‘period eye’ and the ambiguity of the era.

Footnotes –

[1] Baxandall, Michael. 1988. Painting & Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy. Second Edition.

[2] Refers to the cultural and artistic period of the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century.

[3] Fry, Roger. 1995. Giovanni Bellini.

[4] (Fry 1995)

[5] (Fry 1995)

[6] Campbell, Caroline. 2016. Giovanni Bellini: A pioneering Venetian artist | National Gallery.

[7] (Fry 1995)

[8] Goffen, Rona. 1989. Giovanni Bellini.

[9] Oxford English Dictionary. 1989. "Sacred." In Oxford English Dictionary.

[10] Oxford English Dictionary. 2012. "Allegory." In Oxford English Dictionary.

[11] Delaney, Susan. 1977. "The Iconography of Giovanni Bellini's 'Sacred Allegory'." The Art Bulletin 59 (3): 331-335

[12] (Goffen 1989)

[13] Griffey, Erin. “Venice.” ARTHIST 336: Artists and Patrons in Renaissance Italy. Class lecture at University of Auckland. Auckland, New Zealand. 14th October 2021.

[14] (Delaney 1977)

[15] (Delaney 1977)

[16] Parenti, Daniela. n.d. Holy Allegory - The Uffizi, Florence. Accessed June 2022.

[17] Used to describe a a small, naked child in a religious context – a cherub or cupid, for example – in Renaissance art; plural: putti.

[18] (Goffen 1989)

[19] Lindemann, Bernd Wolfgang. 2006. "An Unusual 'Sacra Conversazione' by Giovanni Bellini." In Two Cultures: Essays in Honour of David Speiser, by Kim Williams, 159-166.

[20] (Parenti n.d.)

[21] Land, Norman E. 1984. "On the Poetry of Giovanni Bellini's 'Sacred Allegory'." Artibus et Historiae 5 (10): 61-66.

[22] (Land 1984)

[23] (Parenti n.d.)

[24] (Goffen 1989)

[25] (Goffen 1989)

[26] (Campbell 2016)

[27] (Goffen 1989)

[28] (Goffen 1989)

[29] (Goffen 1989)

[30] (Campbell 2016)

[31] (Goffen 1989)

[32] (Goffen 1989)

[33] Dalhoff, Meinolf. 2002. "Trouble at the hermitage: a note on Giovanni Bellini's 'Sacred Allegory'." The Burlington Magazine 144 (1186): 22-23.

[34] (Baxandall 1988)

[35] (Dalhoff 2002)

[36] (Land 1984)

[37] (Land 1984)

[38] (Griffey 2021)

[39] (Land 1984)

[40] (Lindemann 2006)

[41] (Baxandall 1988)

[42] A studiolo is a Renaissance room dedicated to study and contemplation.

[43] (Lindemann 2006)

[44] (Lindemann 2006)

[45] (Goffen 1989)

[46] (Delaney 1977)

[47] (Goffen 1989)

[48] Latin phrase meaning ‘latest possible date’.

[49] (Delaney 1977)

[50] (Lindemann 2006)

[51] (Lindemann 2006)

[52] (Lindemann 2006)

[53] (Land 1984)

[54] A fantasia or a poesia is a work which produces “poetic” effects through painterly means.

[55] (Land 1984)

[56] (Land 1984)

[57] (Delaney 1977)

[58] Refers to the cultural and artistic period of the Italian Renaissance in the sixteenth century.

Image List –

Figure 1 – Bellini, Giovanni. Sacred Allegory. Oil on wood panel, c. 1488. The Uffizi, Florence.

Painting reproduced via https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/holy-allegory

Figure 2 – Diagram for Bellini, Giovanni. Sacred Allegory. Oil on wood panel, c. 1488. The Uffizi, Florence.

Painting reproduced via https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/holy-allegory

Figure 3 – Diagram for Bellini, Giovanni. Sacred Allegory. Oil on wood panel, c. 1488. The Uffizi, Florence.

Painting reproduced via https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/holy-allegory

Figure 4 – Plague saints (detail). Bellini, Giovanni. Sacred Allegory. Oil on wood panel, c. 1488. The Uffizi, Florence.

Painting reproduced via https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/holy-allegory

Figure 5 – Bellini, Giovanni. San Zaccaria Altarpiece, Sacra Conversazione. Oil on canvas, transferred from panel. 1505. San Zaccaria, Venice.

Painting reproduced via https://www.artsy.net/artwork/giovanni-bellini-san-zaccaria-altarpiece-sacra-conversazione

Bibliography –

Baxandall, Michael. 1988. Painting & Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy. Second Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, Caroline. 2016. Giovanni Bellini: A pioneering Venetian artist | National Gallery. February. Accessed June 2022. https://youtu.be/LO8M3Aiat90.

Dalhoff, Meinolf. 2002. “Trouble at the hermitage: a note on Giovanni Bellini’s ‘Sacred Allegory’.” The Burlington Magazine 144 (1186): 22-23.

Delaney, Susan. 1977. “The Iconography of Giovanni Bellini’s ‘Sacred Allegory’.” The Art Bulletin 59 (3): 331-335.

Fry, Roger. 1995. Giovanni Bellini. New York: Ursus Press.

Goffen, Rona. 1989. Giovanni Bellini. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

Griffey, Erin. “Venice.” ARTHIST 336: Artists and Patrons in Renaissance Italy. Class lecture at University of Auckland. Auckland, New Zealand. 14th October 2021.

Land, Norman E. 1984. “On the Poetry of Giovanni Bellini’s ‘Sacred Allegory’.” Artibus et Historiae 5 (10): 61-66.

Lindemann, Bernd Wolfgang. 2006. "An Unusual 'Sacra Conversazione' by Giovanni Bellini." In Two Cultures: Essays in Honour of David Speiser, by Kim Williams, 159-166. Switzerland: Birkhauser.

Oxford English Dictionary. 2012. “Allegory.” In Oxford English Dictionary. Accessed June 2022. https://www-oed-com.aucklandlibraries.idm.oclc.org/view/Entry/5230

Oxford English Dictionary. 1989. “Sacred.” In Oxford English Dictionary. Accessed June 2022. https://www-oed-com.aucklandlibraries.idm.oclc.org/view/Entry/169556.

Parenti, Daniela. n.d. Holy Allegory - The Uffizi, Florence. Accessed June 2022. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/holy-allegory#online_exhibitions.

Simmons, Laurence. “Still Images: Painting and Photography.” COMMS 302: Visual Communication. Class lecture at University of Auckland. Auckland, New Zealand. 6th May 2021.